Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Calmer Than You Are

The Iran debate has really become rather surreal. You have the "Islamofascist" locution jumping from the fever swamps of rightwing punditry into the mouth of the President of the United States. You have the Secretary of Defense issuing dire warnings of another Munich. These things are being done by the exact same people who, four years ago, were utterly dismissive of claims that invading Iraq was likely to serve Iranian interests better than American ones. Indeed, you have the exact same people who two years ago were assuring us that it made sense to commit American blood and treasure to fight Sunni insurgents on behalf of Iranian-backed Shiite militias now saying we need to commit more blood and treasure in Iraq to stop . . . Iranian-backed Shiite militias. [...]

...if Iran is preparing to mount a Hitler-style bid for world domination they must be engaged in a big military build-up, right? But there is no such build up. Maybe there's no need for a build-up because the Iranian military is already so vast and mighty? Well, no. Iran has a defense budget of about $6 billion a year.

The United States spends over 50 times more than that. But perhaps comparisons to the USA are misleading. Lets compare our would-be regional hegemon to its neighbors. Well, Israel spends $9.6 billion and Saudi Arabia spends $25.2 billion. Pakistan, immediately adjacent to Iran and nuclear armed, actually has engaged in a recent defense buildup. What kind of quest for hegemony is Iran supposed to be on? [...]

Meanwhile, the freaky and unpredictable Iranian regime has actually been in power for a very long time. Since before I was born. The regime is not only long-entrenched, but quite corrupt. Mightn't this lead you think it's being run by reasonably comfortable men who enjoy the fruits of power, intend to stay in power, and know a thing or two about maintaining their power rather than by irrational lunatics who've been waiting in the wings for 27 years preparing to spring their bid for world domination upon us without first having acquired so much as a single modern tank?

And then there's the small matter that our purported would-be Hitlers in Teheran were trying to reach a comprehensive peace agreement with the United States as recently as 2003. Their proposal was rejected by the Bush administration. [...]

So, here's Iran. Outgunned by its two leading religio-ideological antagonists, Israel and Saudi Arabia, in the region. One immediate neighbor is Pakistan, with a larger population base and a nuclear arsenal. Another immediate neighbor, Afghanistan, is occupied by soldiers under the command of an American president who has spurned peace offers and threatened to overthrow the Iranian government. A second immediate neighbor, Iraq, is occupied by a larger number of soldiers from the same country. The Iranian military's equipment is outdated and essentially incapable of mounting offensive operations. So Iran is trying to build nuclear weapons and missiles to deliver them. Under the circumstances, wouldn't you? Don't you think a little deterrence capability would serve the country well under those circumstances?

...Of course it would be better to find a way to persuade, cajole, whatever Iran out of going nuclear -- the spread of nuclear weapons is, as such, bad for the USA. But there's no need -- absolutely no need -- for this atmosphere of panic and paranoia.

Makes me wax nostalgic about the days when Saddam was supposed to be gearing up for total global conquest. Or was it the Vietnamese army in their canoes poised to row to our distant shores like marauding Vikings of yore? Maybe it was the Nicaraguans teamed up with the Cubans heading up through Mexico...

But seriously, Matt makes a good point about incentives here for Iran's build-up. The Bush administration has provided Iran with an endless stream of reasons why they might view obtaining a nuclear weapon as the utmost imperative, while offering little in the way to dissuade them through either positive or negative inducements. Increasingly, I am becoming convinced that some sort of security guarantee should be put forward in the package of carrots and sticks. It might not be enough at this point, but it's worth a shot. And droning on about the next Hitler sure isn't helping any.Dale In Comparison

For anyone frustrated with the government's approach to the criminalization of drug use, and heavy handed tactics adopted in connection with such approach, Franks is the bearer of good news. Go read.

(Via Henley)

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Pimpin' Maliki's Ride

Since the Iraqi government has thus far proven to be an ineffective shell lacking a monopoly on the use of force (or even occupying the primary role in a field of armed competitors) and other manifestations of sovereignty - and since its only potency stems from its tenuously loyal constituent parts - what exactly would the prevailing instigators of a coup have to show for their efforts besides "this lousy T-shirt"? Observerd Swopa:

Since nearly all of the relevant power in the country is essentially outside of government control already, or at best only paying lip service to it, staging a coup in Iraq would be like trying to steal a car that's already been stripped for parts and is sitting on wooden blocks.

With this reality no doubt confronting Maliki and Bush administration officials in Washington, it appears that an effort is underway to bring Maliki's jalopy into the shop for some bling. In particular, there has been a recent push to crack-down on the various militias that have been implementing a peversion of the golden rule: he who has the guns, makes the rules.

So, for the past couple of weeks, US military forces, with the increasing participation of Iraqi forces, have been sweeping areas for arms and militants, and, in some recent cases, engaging Moqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi army in actual armed combat.

While there is an obvious need to rein in the Mahdi army, as well as other militas, in order to consolidate the central government's power over a splintering Iraq, attempting such maneuvers is problematic to say the least. For one, al-Sadr controls the largest single bloc in the Iraqi parliament, and is a major player in the ruling coalition government, so cracking down on his forces takes on a surreal circularity as observed by Matt Yglesias:

And what kind of sense does it make to fight Mahdi Army militiamen on the one hand, and on the other hand have the leaders of the Sadr Movement sitting in parliament and in the cabinet?

This has led to a predictably schizophrenic approach, whereby Prime Minister Maliki repeats his stated goal of disbanding all militias (including al-Sadr's), but then loudly complains when US forces attempt to achieve just that effect. It's hard to tell whether Maliki is paying lip service to the Sadr factions by feigning outrage, or rather is paying lip service to Bush administration officials by feigning cooperation along this front. Or perhaps some mixture of both.

Either way, Iraqi forces did not display a particularly encouraging level of ability or resolve in the recent clash with Sadr's men, and the two sides have retreated to some sort of cease fire - while allowing Sadr to maintain his seemingly incongruous dual identities as both officially recognized political force, and outlaw firebrand. In fact, if one kicks the tires on the new Iraqi government forces, it's easy to detect a familiar pattern of conflicting loyalties, dubious commitment and questionable motive.

From Sunni areas, as recounted in an article in the New York Times last week:

In the Haditha triad, Col. Jebbar Abass...commanded an Iraqi battalion that started out with about 700 soldiers in the fall of 2005. It was now down to about 400 troops. Since almost a third of his battalion is on leave at any one time, that means that Colonel Abass can field about 270 soldiers on any given day, a useful supplement to the Marine forces in and around Haditha but hardly enough to enable the Americans to draw back.

...Marine commanders believe that Iraqi troop levels in Anbar have finally bottomed out and may be slowly starting to improve. But what kind of exit strategy is this when Iraqi soldiers in some of Iraq’s most contested areas have been leaving faster than the Americans?

And Shiite areas, according to an article in today's Times:

A group of [100] Iraqi soldiers recently refused to go to Baghdad, Iraq’s capital, to help restore order there, a senior American military officer said Monday.

"The majority of this particular unit was Shia, and they felt — the leadership of that unit and their soldiers — like they were needed down there in Maysan," General Pittard told reporters in a videoconference from Iraq.

Though the episode involves only a small fraction of the 10-division Iraqi Army, it points to an important issue. The new Iraqi government wants to build a national military, one that is ethnically diverse and can be deployed anywhere in Iraq. It does not want to field a military that is essentially a collection of local units with regional loyalties.

But many Iraqis are reluctant to serve far from their home provinces. Sunnis in Anbar Province, for example, are reluctant to join the army if they will be sent far from home to predominantly Shiite areas. Shiites are often hesitant to serve in overwhelmingly Sunni regions.

This is not the first time that Iraqi soldiers have refused to deploy to a distant area. A large number of soldiers from a predominantly Kurdish unit in northern Iraq, the Second Battalion, Third Brigade of the Second Iraqi Division, refused to go to Ramadi, where American Army troops have been involved in a tough fight to take the city back from insurgents, General Pittard noted.

Speaking of the recently brokered cease-fire between the Mahdi army and the Iraqi government forces, there was an interesting tidbit from the negotiations (that prak alluded to in the sidebar on American Footprints): namely, that a representative from long-time Sadr rival, SCIRI (which controls its own militia, the Badr Brigade), was the go-between chosen [emph. mine throughout]:

Khalil Jalil Hamza, the governor of Diwaniya, later shuttled to Mr. Sadr’s headquarters in Najaf for discussions of a cease-fire, Sadr officials said. By 5:30 p.m., the battled had ended.

Mr. Hamza is a senior official in the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, a Shiite party that is an intense rival of Mr. Sadr’s group. The Mahdi Army and the military wing of the Supreme Council, called the Badr Brigade, have fought pitched battles several times in Baghdad and the south in recent years. Mr. Hamza’s role as the provincial governor suggests that members of the Badr Brigade may have been involved in the fighting on Monday.

This may or may not indicate that the official Iraqi government is throwing in with SCIRI and their militia as the more attractive option in an attempt to squeeze out al-Sadr. However, SCIRI's close ties to Iran, and the oft-reported brutality of the Badr Brigade in dealing with Sunni elements, may make this a case of six of one, half a dozen of the other - without providing for the real consolidation of power, sectarian restraint and monopolization on the use of force desired for the Iraqi centralized government.

Speaking of consolidation of power, the other primary power node in Iraq (the Sunni variety) has been acting to soup up it's own ride for the sequel to Fast and Furious: Baghdad Drift. According to the LA Times (via Swopa):

The insurgency has increased its use of roadside bombs against U.S. and Iraqi forces since Zarqawi's death in June, and in some ways is stronger than when he was alive. . . . The movement lost a wily strategist, but his successor, whom U.S. officials identify as Abu Ayyub Masri, an Egyptian, appears more flexible in recruitment.

"Zarqawi was a hard-liner in his recruitment practices," said a Pentagon consultant who requested anonymity. "This [new] guy is using a big-tent approach. People who were previously excluded from Al Qaeda in Iraq because they lack exceeding levels of fanaticism are now allowed in."

This Sunni hot-rod represents yet another reason why cracking down on Sadr's forces is so difficult: there's more than one car to chase in this hunt, and only a limited number of US military police prowlers. Our forces are spread thin as is trying, unsuccessfully, to defeat a Sunni insurgency. Fighting a Shiite insurgency at the same time would be impossible. Yet al-Sadr may be growing more powerful the longer he is allowed to operate with impunity.

Friday, August 25, 2006

Workin' For the Weekend Mullahs

The US-led "war on terror" has bolstered Iran's power and influence in the Middle East, especially over its neighbour and former enemy Iraq, a thinktank said today.This bitter reality struck a chord with a little humor courtesy of praktike:

Unless stability could be restored to the region, Iran's power will continue to grow, according to the report published by Chatham House.

The study said Iran had been swift to fill the political vacuum created by the removal of the Taliban in Afghanistan and Saddam Hussein in Iraq. The Islamic republic now has a level of influence in the region that could not be ignored.

In particular, Iran has now superseded the US as the most influential power in Iraq, regarding its former adversary as its "own backyard".

The report said: "There is little doubt that Iran has been the chief beneficiary of the war on terror in the Middle East.

...someone once observed that Iran had a real Phase IV plan, unlike the USYeah, in retrospect, maybe we should of had us one of those.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Faking The Funk

Kurtz spares no scare when describing the consequences of electing Democrats this fall [emphasis mine throughout]:

So let’s review. A nuclear Iran is likely to give or lend nuclear weapons to terrorists, resulting in an undeterrable nuclear strike against an American city or cities. Only a credible threat of force can compel Iran to halt its nuclear program, or actually destroy that program, if necessary. In current political circumstances, we lack a credible threat of force. A Democratic victory this fall will solidify that situation, leaving Iran to race to nuclear capability before 2009 when a new president–especially a possible Republican president with greater political capital–accedes to power.

Wait. Let me rewind that first part again:

A nuclear Iran is likely to give or lend nuclear weapons to terrorists, resulting in an undeterrable nuclear strike against an American city or cities.

"Likely"? "an American city or cities"? Those are strong statements considering the series of variables involved, and the magnitude of the events predicted. For example, why would Hezbollah want to launch an attack on an American city or cities? Is that the focus of their operations? What was the last attack on an American city by Hezbollah?

As evidence for this catastrophic prophesy, Kurtz, in a circular fashion, relies on an article appearing in the National Review penned by fellow hawk Paul Johnson. In that article, Johnson mostly speculates about the situation in a manner similar to Kurtz, while offering little in the way of persuasive proof for his contentions.

No doubt sensing the weakness of his case - built on the mutually reinforcing guesswork of two strident hawks - Kurtz enlists an unwitting ally, Scott Sagan, who wrote an article in this month's Foreign Affairs (a periodical that Kurtz incorrectly labels as "Democrat leaning" to bolster the bi-partisan credentials of his thesis).

But don’t believe NR. Consider instead what a Democrat-leaning policy journal has to say. In an important article in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs, Scott Sagan argues that Cold War-style deterrence won’t work with Iran. According to Sagan, the most radical element in Iran–the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps–is likely to get a hold of nuclear materials and give them to terrorists, whatever Iran’s central government wants.

Wait, let me rewind that last part again:

According to Sagan, the most radical element in Iran–the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps–is likely to get a hold of nuclear materials and give them to terrorists, whatever Iran’s central government wants.

According to Kurtz, Sagan said that the IRGC is "likely" to give nuclear materials to terrorists? Again, note the starkness of the prediction. Having just finished reading Sagan's article last night, it struck me as somewhat more emphatic and categorical than how I remembered Sagan's actual admonition. Here are the relevant excerpts from the Sagan piece:

Tehran, like Islamabad, would be unlikely to maintain centralized control over its nuclear weapons or materials. In order to deter Tehran from giving nuclear weapons to terrorists, in January 2006 the French government announced that it would respond to nuclear terrorism with a nuclear strike of its own against any state that had served as the terrorists' accomplice. But this "attribution deterrence" posture glosses over the difficult question of what do if the source of nuclear materials for a terrorist bomb is uncertain. It also ignores the possibility that Tehran, once in possession of nuclear weapons, would feel emboldened to engage in aggressive naval actions against tankers in the Persian Gulf or to assist terrorist attacks as it did with the Hezbollah bombing of the U.S. barracks at the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia in 1996.

There is no reason to assume that, even if they wanted to, central political authorities in Tehran could completely control the details of nuclear operations by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The IRGC recruits young "true believers" to join its ranks, subjects them to ideological indoctrination (but not psychological-stability testing), and -- as the IAEA discovered when it inspected Iran's centrifuge facilities in 2003 -- gives IRGC units responsibility for securing production sites for nuclear materials. The IRGC is known to have ties to terrorist organizations, which means that Iran's nuclear facilities, like its chemical weapons programs, are under the ostensible control of the organization that manages Tehran's contacts with foreign terrorists.

Not overly optimistic, nor without ample cause for concern, but not quite what Kurtz says it is. To summarize, Sagan does say that Iran's central government would be "unlikely" to maintain control over the nuclear materials, with such control "ostensibly" vesting in the IRGC. And he does say that the IRGC has ties to terrorist organizations. But he does not say that the IRGC is "likely to give [nuclear materials] to terrorists" as Kurtz claimed - nor that such terrorists would attack multiple American cities if they did acquire such weapons. For that, one must read Sagan's arguments and take an enormous leap that the author does not intend - at least not as evidenced by his words.

Consider also that Sagan is comparing Iran's situation to that of Pakistan - in terms of the similar lack of centralized control over the nuclear program and ties to terrorism. While Pakistan's nuclear capacity is highly problematic for these reasons and more, it should be noted that, as of yet, Pakistan has not given nuclear weapons to terrorists in order to attack multiple American cities - even though the terrorists that Pakistan has ties to are al-Qaeda who actually have the intent and incentive to attack American cities as opposed to Iran's Hezbollah proxy. Why, then, is Iran likely to diverge from this model?

And so we see, as highlighted by praktike in terms of the intelligence shell game currently being perpetrated by the usual suspects (see, also Laura), a similar method of insinuation, exaggeration, embellishment and mendacity is being pursued with the purpose of goading the US into yet another disastrous war in the Middle East.

There is no doubt that Iran poses serious national security dilemmas for US policymakers at this time - and for the foreseeable future. The tragedy is, though, that with this type of dishonest analysis, and ginned up intelligence claims made in Washington, it becomes harder to accurately survey the situation and craft solutions to fit the crisis. Over-reaction and underestimation of the threat become all too likely depending on the perspective of the observer.

Something tells me we may want to re-assess how well this mode of policy making has been serving us. To coin a phrase, honesty leads to the best policy.We Get Letters

I have always thought that Islamofascist was a very foolish way to frame these types of discussion because it implies a false similarity where none exists. The same is true with how Islamic fundamentalism attempts to make a false comparison to Christian fundamentalism. As for Islamist, it's a made-up term that is so broad that it encompasses everyone from bin Laden to the Turkish AKP but is still too narrow to include Saddam Hussein.

One of my suggestions would be that in using labels in public discourse the terms should serve to illuminate rather than obfuscate the discussion (especially if one wishes to end comparisons to WW2). While I think fascism is an acceptable enough description to apply to Baathism, I think that a far better way to go about labels is to start using terms like Khomeinism, Qutbism, Salafism, and so on. Saying that someone is a Khomeinist, for instance, tells you a great deal about their political views, how they think society should be ordered, and so on. Not so much with the Islamofascist label. During the Cold War people were able to understand and recognize distinctions between Trotskyism, Leninism, Stalinism, and Maoism within communism even if they didn't view these ideologies as being all that different WRT how various communist groups and states viewed their capitalist opponents.

The writer makes a good point about the broad brush approach, and how it muddies, not clarifies, the picture. It succeeds in creating a category that roughly translates into "Muslims with authoritarian views we don't like." While in some ways the groups most frequently included under the "Islamofascist" umbrella do share some traits in common with "fascism" per se, there are, more importantly, fundamental differences in the world views, tactics, aspirations and objectives of these various actors.

Failing to differentiate highlights our ignorance and creates the impression that we don't take these differences seriously. We should, though. For one, if we don't, we risk alienating many potential allies in the Muslim community for no discernible value in return. We begin to resemble the caricature of the mobs that attacked Sikhs in the wake of 9/11 because of the head gear that is vaguely reminiscent of that worn in some Muslim cultures, and of the nation led by the President who signed off on an invasion of Iraq without knowing about the fact that the Sunni and Shiite sects even existed. In short, it undermines our credibility by reinforcing the image of contempt and disdain for an entire group of people numbering over a billion - a group whose cooperation is kind of important at this time.

Further, these differences represent an opening for us to deal with each group separately, as different means can be employed to contain, counter and deal with the particular ideologies, and manifestations thereof, that run counter to our interests. In some cases, it may even be possible to use the differences themselves as leverage.

This lack of clarity, however, is telling of the motives of many who use the "Islamofascist" phrase: conflating groups like al-Qaeda with groups like Hamas has its advantages if one is looking to compel a certain course of action vis-a-vis Hamas. But is that the best vantage point from which to make informed strategic decisions? I don't believe so.Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Category Mistake Redux

Now you know why I drink. Read the rest, and pour yourself a stiff one too.As for Iraq, it's no news that Bush has no strategy. What did come as news—and, really, a bit of a shocker—is that he doesn't seem to know what "strategy" means.

Asked if it might be time for a new strategy in Iraq, given the unceasing rise in casualties and chaos, Bush replied, "The strategy is to help the Iraqi people achieve their objectives and dreams, which is a democratic society. That's the strategy. … Either you say, 'It's important we stay there and get it done,' or we leave. We're not leaving, so long as I'm the president."

The reporter followed up, "Sir, that's not really the question. The strategy—"

Bush interrupted, "Sounded like the question to me."

First, it's not clear that the Iraqi people want a "democratic society" in the Western sense. Second, and more to the point, "helping Iraqis achieve a democratic society" may be a strategic objective, but it's not a strategy—any more than "ending poverty" or "going to the moon" is a strategy.

Strategy involves how to achieve one's objectives—or, as the great British strategist B.H. Liddell Hart put it, "the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy." These are the issues that Bush refuses to address publicly—what means and resources are to be applied, in what way, at what risk, and to what end, in pursuing his policy. Instead, he reduces everything to two options: "Cut and run" or, "Stay the course." It's as if there's nothing in between, no alternative way of applying military means. Could it be that he doesn't grasp the distinction between an "objective" and a "strategy," and so doesn't see that there might be alternatives? Might our situation be that grim?

You Know It's Bad When...

OK, technically speaking the piece I'm referencing didn't appear in the print edition, but it was featured on TNR's blog just a couple of days ago - and generated a good deal of blog-related buzz. In that piece, Spencer Ackerman made the case that using the term "Islamofascist" was utterly counterproductive in that it served to alienate and antagonize moderate Muslims in the United States (and abroad) who are our necessary and useful allies in the effort to combat terrorism in the name of Islam.

On the flip-side, there is nothing really gained by using the term which is neither historically accurate, nor particularly helpful in describing the phenomenon that we are now seeking to combat. So, to summarize: high-cost, low-reward rhetoric = not smart.

Yet, despite Ackerman's insight, the very next day (just two blog entries later!), TNR head honcho Martin Peretz offers up this gem [emph. added]:

Oh, and by the way, according to The New York Times this morning, Iran's "supreme leader," Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, (not Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who increasingly and wrongly is being treated as a comic figure instead of a madman with post-modern arms at his disposal, an Islamofascist, in fact), announced yesterday that his country will "forcefully" pursue its uranium enrichment nuclear programs.

Well, you can lead a one-trick pony to water, but you can't make him drink. Speaking of "you know it's bad when," the same Spencer Ackerman makes the point today that "you know its bad in Iraq when" we're pining for the days when Iraqis considered us their primary enemy (a point Brian Ulrich also touched on today). Said Ackerman:

Not to worry. If the whole mission goes sour as the intricate web of internecine fighting tears at the seams of Iraqi society, we can just blame the Islamofascists. That'll make it easier to keep track: One size fits all.[I]n the grand scheme of things, it's better for Iraq (as opposed to being better for us) that Iraqis hate us more than each other: It suggests that after we leave, Iraq will have some future. According to an unfairly-neglected recent story by McClatchy's Nancy Youssef, one of the best American reporters in Iraq, that dynamic is pretty much reversed [...]

Not that this is so new, but the piece is still striking. The only ones who believe the Iraqi security forces are anything beyond sectarian forces, trusted by the people, are those who have a stake in such an answer: the Maliki government, the Iraqi officer corps, the U.S. military command, the Bush administration. Remember that the Iraqi security forces aren't just part of Bush's "strategy" for Iraq, they're the whole thing.

My Own Personal Apocalypse

Monday, August 21, 2006

If He Only Had No Brain

For an example of the type of mistakes that can, even in small part, impact our effort to combat the spread and appeal of radical Islamist terrorism that I addressed earlier, Spencer Ackerman gives us some advice on the efficacy of rhetoric:

I spent the last week in Dearborn, Michigan, home of the largest and oldest Muslim community in the United States, and I have a news flash: President Bush's recent formulation of the enemy in the war on terrorism as "Islamic Fascism," or, as it's more often known, "Islamofascism," is extremely offensive here. [...]

Last week in the Weekly Standard, the apparent inventor of the phrase, Stephen Schwartz, dismissed those who'd be offended by "Islamofascism" as "primitive Muslims". That should tell you all you need to know about those who use the term....The people it infuriates aren't primitive. They're the moderate, pro-American, well-integrated Muslims who form one of the greatest bulwarks against Al Qaeda that the U.S. possesses, and they see the term as draining their Americanness away.

And for what? For a dubious linkage to a much different historical phenomenon? It doesn't diminish the crimes of the Taliban to observe that a Nazi would find Taliban-ruled Afghanistan unrecognizable. "Islamofascism" merely strokes an erogenous zone of the right wing, which gains pleasure from a juvenile reductio ad Hitlerum with the enemies of the U.S.

"Reductio ad Hitlerum." Priceless.

But seriously, what we're talking about here is low-reward, high-cost behavior on the part of the Bush administration and its ideological allies. Alienating moderate American Muslims for little more than a self-satisfying analogy. Retiring this phrase should be a no-brainer. Even for Bush's brain.On Being Overly Categorical, and Making Category Mistakes

"The idea that the jihadists would all be peaceful, warm, lovable, God-fearing people if it weren't for U.S. policies strikes me as not a valid idea...." [...]Note the use of the word "justified." As Gene Callahan explained five years ago, with a commendably cool head amidst the passion, paranoia and jingoism rampant in the days following the attacks on 9/11: this is fundamentally a category mistake. The question is not whether or not the actions of terrorists are morally justified in light of US foreign policy, but whether one can explain how certain of our actions can create a dynamic within which terrorism might become an attractive option and otherwise flourish. Said Callahan:

The official is correct that it is wrong "to think that somehow we are responsible -- that the actions of the jihadists are justified by U.S. policies." But few outside the fog of paranoia that is the blogosphere think like that.

The mode of historical discourse is that of just such explanations. The historian qua historian is not concerned with the morality of a course of action. He is concerned with explaining why that course of action, and not some other, actually was chosen. The result of his efforts is a coherent narrative that describes how historical events arose from various actors' understanding of their circumstances.Through the same basic category mistake, Will and his Bush administration accomplice erect a useful strawman with which to criticize and belittle the work of political opponents, historians and commenters, professional and amateur alike, who seek to probe explanations of the terrorist phenomenon that consider cause and effect relationships and thus, hopefully, support and help craft policies designed to minimize their deleterious consequences. While many commenters and Democratic officials have explored the root causes of terrorism, there are only nominal numbers on the fringe that seek to morally justify those actions by referring to our foreign policy.

Moral justification does not concern itself with such explanations, but, instead, with whether or not some action conformed to a tradition of moral practice.

The other frequent error encountered when discussing the concept that US foreign policy can, in some circumstances, give rise to or create underlying support for, terrorism is that of being overly categorical. Most often, this manifests itself in a series of all or nothing propositions.

First, is the counter-argument that there is no set of US foreign policy choices that could on their own satisfy every Islamist terrorist everywhere. Some terrorists would still want to attack us no matter what. Second, and related to the first, is the claim that there are no policies that we could adopt that would eradicate anti-Americanism and the hostility that terrorists must exploit in order to secure for themselves the recruits needed to carry out operations, the financing to conduct their affairs and the relative anonymity needed to avoid detection that a friendly population can provide.

Those that use these categorical frames are usually doing so in support of a position that seeks to shield unwise and faulty American foreign policies from criticism based on the logical consequences of those policies. "Why change our foreign policy," they ask, "when nothing is going to completely extinguish all terrorism committed against US interests everywhere?" This fallacy was eloquently asserted by Irshad Manji in an op-ed in the New York Times also last week:

Last week, the luminaries of the British Muslim mainstream — lobbyists, lords and members of Parliament — published an open letter to Prime Minister Tony Blair, telling him that the "debacle" of both Iraq and Lebanon provides "ammunition to extremists who threaten us all." In increasingly antiwar America, a similar argument is gaining traction: The United States brutalizes Muslims, which in turn foments Islamist terror.While I generally applaud Manji's call for a greater sense of individual and group responsibility within her community, and the notion that US foreign policy does not and should not justify terrorism, I found her historical analysis of explanations to be lacking.

But violent jihadists have rarely needed foreign policy grievances to justify their hot heads. There was no equivalent to the Iraq debacle in 1993, when Islamists first tried to blow up the World Trade Center, or in 2000, when they attacked the American destroyer Cole.

First of all, in rebuttal to her counterpoints, it should be noted that there was a certain Iraq-related incident of concern around the time of the 1993 World Trade Center attack - even if not nearly as radicalizing an event as the current catastrophe. Further, it was in partial reaction to events surrounding the first Iraq war that bin Laden developed attitudes that led, in part, to the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole (and subsequent attacks on the US) - the rejection by the Saudi royals of his offer to provide a cadre of troops comprised of mujahadeen from Afghanistan to secure the Saudi border with Iraq in favor of a sizable US force. The prolonged presence of those US forces was viewed as an assault on Islam by bin Laden, a sign of the Saudi regime's subservience to US interests and as a blow to his own outsized ego.

Further, Manji artfully dodges the 500lb gorilla in the room that is the United States' foreign policy in relation to Israel and the Palestinians - again, cited by bin Laden and Zawahiri at various times as giving rise to portions of their perverted jihadist worldview. Not to mention the net effect of a century's worth of strategic thinking designed to maintain an affordable and stable supply of oil, and counter Soviet attempts to do the same, that led to the adoption of many unsavory policies including a coup that toppled a democratically elected president in Iran as well as the coddling and support of many related and unrelated despots (including Saddam himself under Reagan). Billmon does a pretty good job of sketching out this chapter in our history.

But more important than refuting the specific historical examples cited by Manji, or engaging the meta-historical analysis of Billmon et al, is to challenge the premise that we must only consider options in this "all or nothing" framework. While Manji is correct that some Islamist terrorists are going to exist regardless of our foreign policy decisions (or at least those that we could undertake within reason), and that, relatedly, some degree of anti-Americanism is going to persist anyway (always a useful tool for leaders and populations alike to deflect responsibility and blame), those unfortunate facts don't mean that there is nothing to be gained by being conscious of, and accounting for, the impact of our foreign policy on the region. Quite the opposite.

For terrorists to be successful, they must have a certain level of cooperation and support from the underlying population. While we might not be able to adopt policies that are going to ingratiate ourselves to everyone everywhere, or completely eliminate anti-Americanism, that doesn't mean that we have nothing to gain by employing best practices in this regard. Even incremental shifts in the intensity of the anti-American feelings espoused by our detractors, and the size of that very detractor pool, can have a significant impact on the ability of terrorists to act - and the levels of anti-terrorist support that we receive from foreign goverments and populations alike.

Along the lines of assessing the importance of influencing local populations, tilting the scales in our favor can: (a) limit the size and scope of potential terrorist attacks by turning those populations against such missions, even if small scale operations remain a regrettable possibility; (b) increase the latitude of foreign governments to assist us in light of the attitudes of their own underlying constituencies; and (c) increase the number of potential informants and human intelligence candidates by presenting a sympathetic and attractive world view. James Fallows touches on this last factor in his most recent article:

The final destructive response helping al-Qaeda has been America’s estrangement from its allies and diminution of its traditionally vast "soft power." "America’s cause is doomed unless it regains the moral high ground," Sir Richard Dearlove, the former director of Britain’s secret intelligence agency, MI-6, told me. He pointed out that by the end of the Cold War there was no dispute worldwide about which side held the moral high ground—and that this made his work as a spymaster far easier. "Potential recruits would come to us because they believed in the cause," he said. A senior army officer from a country whose forces are fighting alongside America's in Iraq similarly told me that America "simply has to recapture its moral authority."Likewise, a foreign policy that acknowledges and accounts for how terrorism thrives within, and in reaction to, certain dynamics - those that foster feelings of humiliation and powerlessness, and the general radicalizing effects of war and armed conflict - is one that will better combat (though possibly not completely purge) terrorism from drying up sources of funding and recruitment, to potentially dwindling the number of self-starters.

Contending with consequences is the wisdom gleaned from classic counter-insurgency doctrine - as well as any other model of human interaction. With respect to this doctrine, as in most arenas, it is better not to make the perfect the enemy of the good, nor confuse an explanation with a justification. As those speaking categorically all too often do.

(h/t Jim Henley)

Friday, August 18, 2006

Trois Card Monte

Kevin Drum expressed more than a little displeasure at the recent noise emanating from Paris that France might not follow through with the provision of troops to fill out the beefed-up UN force in Lebanon that was pledged as part of a cease-fire agreement brokered by France in recent weeks. Kevin even went as far as to dispense the rare Political Animal "Wanker of the Day" award to Jacques Chirac (Drum is decidedly stingier than Atrios in bestowing such ignominious honors). Said Drum:

Let's summarize: Chirac personally rammed through the ceasefire resolution; insisted that it call for a UN force; did everything he could to imply that France would contribute several thousand combat troops; but in the end is only willing to stand up a 200-man military engineering company. Because Hezbollah might shoot back.Allow me to suggest an alternative narrative, however - one that doesn't cast France as the double-dealing and duplicitous agent of evil. First, I would posit that the French didn't necessarily "ram through" their cease-fire proposal against anyone's will, but rather gave each party what they wanted, but could not ask for openly. The US wanted this conflict to end (not initially, obviously, but by this time), the Israelis wanted it to end (see, previous parenthetical) and, most likely, even Hezbollah (who may be the net winners here) wanted this to end.

But, and that's a crucial "but," each side needed something to save face. This is typically one of the major impediments to putting the brakes on a mutually destructive conflict once it has erupted, regardless of which faction is involved. So against this backdrop, in step the French to apply the rouge to the cheeks of the respective parties in a little Kabuki theater Left Bank style.

My guess is that the US, Israel and Hez were either aware that the French weren't going to actually commit the number of troops advertised, or that there was at least sufficient cause to doubt France's resolve on this matter (a shocking concept to many readers, I'm sure). It's possible the French out-maneuvered the US and Israelis, but it's also possible - likely even - that the US and Israelis were willing dupes, going along with the fiction so that each party could achieve their strategic objective (after adjusting those objectives to take into account the "facts on the ground" deduction).

The US got an end to a conflict that was roiling the region, weakening the democratically elected Lebanese government and boosting the stature of our enemies like al-Sadr in Iraq and Ahmadinejad in Iran. Similarly, Israel realized that things weren't exactly going well in their efforts to dismantle Hezbollah very early on, and thus have been looking for the escape hatch ever since. Israel isn't naive enough to have thought that the French were going to save their bacon on this, however, but it gave Olmert an opening to cut short this utterly counter-productive military campaign with some shred of plausible deniability.

As an added bonus, the US and Israel can later point to the French as the villainous and craven prevaricators. "See, those French spoiled the souffle of peace and democracy yet again with their deceitful lack of resolve!" Feckless, UN, multilateral, Old Europe, etc., etc.

Even Nasrallah probably realized that there was a point of diminishing returns fast approaching around which his symbolic victory would begin to pivot toward the pyrrhic, and at which point his already pocketed gains made in Lebanon's internal political scheme would become unnecessarily jeopardized. A bird in hand is worth two in the bush after all, even if not a dove.

Everyone essentially got what they wanted: A way out that doesn't look like surrender, and a scapegoat to wash away the bitter aftertaste. The French? Well, they got to relive their heyday as a major international player complete with globally impactful influence, guile and power. On a less cynical note, they were able to facilitate an end to a conflict that was destabilizing the region, radicalizing elements in a dangerous way and leading to massive loss of life. For these reasons, finding a way out was is in France's interest as well regardless of other nostalgic reminiscing of glory days long gone.

But keep this in mind when over the next couple of weeks, US and Israeli spokesmen adopt a Claude Rains pose and loudly proclaim their "Shock, Shock!" that the French forces never materialized. Yeah, we know. And there's gambling at Rick's Cafe Americain.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Questions and Answers

What I'd like to know about is the evidence of bomb-making. Those liquid ingredients, detonator components.

The more I think about the liquid bomb thing, the fewer possibilities I come up with.

Today, in seeming response to Rofer's question, Kevin Drum links to a piece that sheds light on some problems with the particular liquid explosive that was, allegedly, to be used in connection with the aforementioned terrorist plot:

I lack the expertise to comment further on this piece, but the author does include citations to relevant literature. I welcome informed input. Otherwise, stay tuned.We're told that the suspects were planning to use TATP, or triacetone triperoxide, a high explosive that supposedly can be made from common household chemicals unlikely to be caught by airport screeners. A little hair dye, drain cleaner, and paint thinner - all easily concealed in drinks bottles - and the forces of evil have effectively smuggled a deadly bomb onboard your plane. [...]

Making a quantity of TATP sufficient to bring down an airplane is not quite as simple as ducking into the toilet and mixing two harmless liquids together.

First, you've got to get adequately concentrated hydrogen peroxide. This is hard to come by, so a large quantity of the three per cent solution sold in pharmacies might have to be concentrated by boiling off the water. Only this is risky, and can lead to mission failure by means of burning down your makeshift lab before a single infidel has been harmed.

But let's assume that you can obtain it in the required concentration, or cook it from a dilute solution without ruining your operation. Fine. The remaining ingredients, acetone and sulfuric acid, are far easier to obtain, and we can assume that you've got them on hand.

Now for the fun part. Take your hydrogen peroxide, acetone, and sulfuric acid, measure them very carefully, and put them into drinks bottles for convenient smuggling onto a plane. It's all right to mix the peroxide and acetone in one container, so long as it remains cool. Don't forget to bring several frozen gel-packs (preferably in a Styrofoam chiller deceptively marked "perishable foods"), a thermometer, a large beaker, a stirring rod, and a medicine dropper. You're going to need them.

It's best to fly first class and order Champagne. The bucket full of ice water, which the airline ought to supply, might possibly be adequate - especially if you have those cold gel-packs handy to supplement the ice, and the Styrofoam chiller handy for insulation - to get you through the cookery without starting a fire in the lavvie.

Once the plane is over the ocean, very discreetly bring all of your gear into the toilet. You might need to make several trips to avoid drawing attention. Once your kit is in place, put a beaker containing the peroxide / acetone mixture into the ice water bath (Champagne bucket), and start adding the acid, drop by drop, while stirring constantly. Watch the reaction temperature carefully. The mixture will heat, and if it gets too hot, you'll end up with a weak explosive. In fact, if it gets really hot, you'll get a premature explosion possibly sufficient to kill you, but probably no one else.

After a few hours - assuming, by some miracle, that the fumes haven't overcome you or alerted passengers or the flight crew to your activities - you'll have a quantity of TATP with which to carry out your mission. Now all you need to do is dry it for an hour or two.

The genius of this scheme is that TATP is relatively easy to detonate. But you must make enough of it to crash the plane, and you must make it with care to assure potency. One needs quality stuff to commit "mass murder on an unimaginable scale," as Deputy Police Commissioner Paul Stephenson put it. While it's true that a slapdash concoction will explode, it's unlikely to do more than blow out a few windows. At best, an infidel or two might be killed by the blast, and one or two others by flying debris as the cabin suddenly depressurizes, but that's about all you're likely to manage under the most favorable conditions possible.

Unmasked

Max Sawicky has a nice follow up to a conversation me and Haggai had recently in this comment thread. The discussion centered around the ignorance of President Bush that was revealed by his surprise at, and "frustration" with, the fact that Iraqi Shiites demonstrated in large numbers - chanting anti-Israeli and anti-American slogans - in opposition to Israel's military actions vis-a-vis Lebanon. Observed "Haggai":

Gee, that's a tough one. A massive show of Arab public support for Hezbollah in the midst of fierce fighting with Israel--and from Shiites, no less! Who'da thunk it? [...]

...[Bush] doesn't even understand that whenever Arab-Israeli fighting erupts, public opinion in the Arab world is immediately going to be inflamed against Israel, and that the US in this context is always treated as Israel's enabler (or stooge, depending on the particulars of the rhetoric at hand).

I responded by pointing out that a person who didn't know that there were two main branches of Islam might be ignorant of this basic and well known dynamic as well. Unfortunately, that person also happens to be our President, and the head of an administration that is undertaking an enormously risky, radical and audacious policy of destabilization and political reordering in the very region of the world which the President seems to know so little about.

From Sawicky, we see even more evidence to confirm the frightening degree to which Bush fails to understand the players and policies involved. From a press conference with Bush:

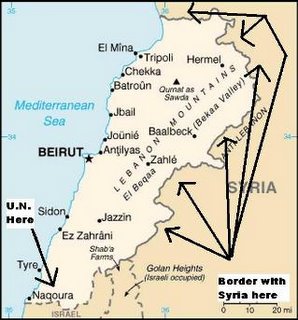

Please refer to the above map* of the border between Lebanon and Syria, and the primary location of the UNIFIL troops. And then say a prayer.QUESTION: How can the international force, or the United States if necessary, prevent Iran from resupplying Hezbollah?

BUSH: The first step is -- and part of the mandate in the U.N. resolution was to secure Syria's borders. Iran is able to ship weapons to Hezbollah through Syria. . . . In other words, part of the mandate and part of the mission of the troops, the UNIFIL troops, will be to seal off the Syrian border.

(* Map borrowed from Max Sawicky with the utmost of gratitude)

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Quote of the Day: Staring At The Sea Edition

Maureen Dowd commenting on the announcement that Bush, playing against type, was reading The Stranger by French existentialist Albert Camus on his most recent vacation in Crawford:

"If there was ever a confirmation of Camus’s sense of the absurdity of life, it’s that the president is reading him."

She even finishes as a runner-up in the same contest with a clever quip at the end of this paragraph [emph. mine]:

"Debunking the theory that W. had a sports section or Mad magazine’s “Spy vs. Spy” tucked inside the 1946 classic of angst, Mr. Snow noted that he and the president had “a brief conversation on the origins of French existentialism, Camus and Sartre.” Pressed for more details by an astonished columnist having trouble envisioning Waco as the Left Bank, the press secretary laughed. “Confidential conversation,” he said, extending the administration’s lack of transparency to literature."

How To Avoid Kneeling Before Zod

It's a cliche in any comic book inspired superhero movie (or other mythic hero vehicle) for there to come a point when the nefarious villain grasps that the exploitable weakness of the otherwise formidable protagonist lies in that chartacer's soft-spot for the innocent lives of the hoi polloi.

This opening was utilized with particular cunning by General Zod and his cohorts in Superman II, though Lex Luthor never shied away from a little leveraging of mass civilian death to compel Superman to act as desired. Other examples abound in the realm of geekdom.

In an interesting twist on this oft-repeated motif, Grim at Black Five attempts to extricate "truth, justice and the American way" from the messy entanglements that arise when an otherwise heroic United States becomes overly concerned with the loss of innocent life. Actually, Grim is talking in particular about the lives of children - and not just of our enemy, but our own as well.

His argument has something to do with the notion that our concern for the lives of children makes them useful as targets and human shields, the value of which would decrease if we cared less for them and that in the long run, this might make them less susceptible to die in armed conflict. Or so it goes.

On the other hand, one could easily imagine how callous disregard for the lives of children could also lead a combatant to, unsurprisingly, care little about killing the children of his enemy for any reason or none. At the very least, they represent potential future combatants that could be preemptively elimiated. And, after all, who cares about a couple thousand dead children anyway?

Not to mention the fact that Grim's particular formula would only really work if both sides agreed to jetison their quaint and overly sentimental attachments to children. If one side in the equation persisted in caring for children, their utility would be preserved.

Nevertheless, here is a relevant excerpt from his imaginary dialogue with a "gentle peaceful soul."

Holy up-ended morality Batman!"If we did not care if our children died, they would not be targets. There would be no reason to target them, because we would not be moved by their deaths.

"If we did not care if their children died," I add, "there would be no reason to clutter military emplacements with their presence. If it were not that we are horrified by the deaths of children, the enemy's children would be clear of all places of battle -- because they are, except for the fact that we love them, a hindrance." [...]

..."Here: That we pursue war without thought of the children. That we do not turn aside from the death of the innocent, but push on to the conclusion, through all fearful fire. If we do that, the children will lose their value as hostages, and as targets: if we love them, we must harden our hearts against their loss. Ours and theirs."

"We can only do," I must warn her, and you. "We can only do, and pray, that when we are done we may be forgiven."

Dude?

July appears to have been the deadliest month of the war for Iraqi civilians, according to figures from the Health Ministry and the Baghdad morgue, reinforcing criticism that the Baghdad security plan started in June by the new Iraqi government has failed.

An average of more than 110 Iraqis were killed each day in July, according to the figures. The total number of civilian deaths that month, 3,438, is a 9 percent increase over the tally in June and nearly double the toll in January.

Hey, but look on the bright side, the numbers cited above are likely inaccurate:

United Nations officials and military analysts say the morgue and ministry numbers almost certainly reflect severe undercounts, caused by the haphazard nature of information in a war zone.

Many casualties in areas outside Baghdad probably never appear in the official count, said Anthony H. Cordesman, a military analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a research group in Washington. That helps explain why fatalities in Baghdad appear to account for such a large percentage of the total number, he said in a recent report.

Ugh. Nonetheless, the Bush administration has the situation pretty well under control. Ever-attuned to the exigencies of a given crisis, Bush has unveiled a new plan to apply a torniquette to the bleeding, and a policy guaranteed to lead to victory! Actually, not really a policy per se (policy is for the effete), it's just a slogan: Adapt To Win. That ought to do it.

Speaking of adapting to win, Tom Lasseter has a depressing play by play of the results of our previos victory-inclined adaptations (via Swopa):

While various military operations have at times improved security in parts of the country, the bloodshed has mounted with each U.S.-declared step of progress, according to figures that the Brookings Institution research center compiled from news and government reports.

When L. Paul Bremer, then the top U.S. representative in Iraq, appointed an Iraqi Governing Council in July 2003, insurgent attacks averaged 16 daily. When Saddam Hussein was captured that December, the average was 19. When Bremer signed the hand-over of sovereignty in June 2004, it was 45 attacks daily. When Iraq held its elections for a transitional government in January 2005, it was 61. When Iraqis voted last December for a permanent government, it was 75. When U.S. forces killed terrorist mastermind Abu Musab al Zarqawi in June, it was up to 90.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

We're In Good Hands?

From the sublime to the ridiculous, details concerning the denoument of the recent terrorist plot foiled in Great Britain (and the subsequent homeland security reaction) offer little in the way of comfort.

First, we learn that there was substantial disagreement over the timing of the arrests made of the suspects in the British plot:

NBC News has learned that U.S. and British authorities had a significant disagreement over when to move in on the suspects in the alleged plot to bring down trans-Atlantic airliners bound for the United States.

British officials knowledgeable about the case said British police were planning to continue to run surveillance for at least another week to try to obtain more evidence, while American officials pressured them to arrest the suspects sooner. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the case.

In contrast to previous reports, one senior British official suggested an attack was not imminent, saying the suspects had not yet purchased any airline tickets. In fact, some did not even have passports.

Anyone witnessing the media circus - initially primed by the GOP (with ominous warnings about aid and comfort to al-Qaeda as seen through the Connecticut Senatorial primary) - that followed close on the heels of Lamont's victory with the breaking story of the British arrests, must be at least a little suspicious of the serendipitous timing.

I'm not saying that there were not legitimate reasons that American officials wanted to move at the time chosen, and that decisions were not made purely on honest, tactical assessments, but the Bush administration's history of dubiously timed "breakthroughs" has created a credibility gap and engendered suspicions were none should exist.

Recall, that almost immediately after the Democratic convention in 2004, there was news of a major arrest of an al-Qaeda operative in Pakistan. After the dust settled, it was revealed that the manner and timing of that arrest/disclosure (irresistible, apparently, from a political perspective for its ability to overshadow any media focus on Democratic hopeful John Kerry), may have compromised the value of intelligence gleaned from the subject's interrogation/materials-seized and undermined efforts to conduct sting operations using various persons involved.

Also, recall, the curiously beneficial timing, and remarkable frequency, of those utterly useless color-coded terror alerts, discussed by Josh Marshall here:

The 18 months prior to the 2004 presidential election witnessed a barrage of those ridiculous color-coded terror alerts, quashed-plot headlines and breathless press conferences from Administration officials. Warnings of terror attacks over the Christmas 2003 holidays, warnings over summer terror attacks at the 2004 political conventions, then a whole slew of warnings of terror attacks to disrupt the election itself. Even the timing of the alerts seemed to fall with odd regularity right on the heels of major political events. One of Department of Homeland Security chief Tom Ridge's terror warnings came two days after John Kerry picked John Edwards as his running mate; another came three days after the end of the Democratic convention.

So it went right through the 2004 election. And then not long after the champagne corks stopped popping at Bush campaign headquarters, terror alerts seemed to go out of style. The color codes became yesterday's news. With the exception of one warning about mass-transit facilities in response to the London bombing on July 7, 2005, that was pretty much it until this summer.

Former head of the Deparment of Homeland Security didn't exactly rush to pour cold water on this speculation in an interview last year:

[Ridge said] he often disagreed with administration officials who wanted to elevate the threat level to orange, or "high" risk of terrorist attack, but was overruled.

Ridge said he wanted to "debunk the myth" that his agency was responsible for repeatedly raising the alert under a color-coded system he unveiled in 2002.

"More often than not we were the least inclined to raise it," Ridge told reporters. "Sometimes we disagreed with the intelligence assessment. Sometimes we thought even if the intelligence was good, you don't necessarily put the country on (alert). ... There were times when some people were really aggressive about raising it, and we said, 'For that?' "

After the recent British incident, we were treated to a parade of GOP notables, and a depressingly cooperative and compliant press, touting the mantra that the GOP is tough on terrorism, the foiled attacks should remind Americans we're still at war and, relatedly, the GOP are the ones to trust in such perilous times. There are, however, more than a few problems with that narrative.

For one, the frightening new method of attack "uncovered" (liquid explosives) wasn't really so new after all. Larry Johnson had this to say about these "revelations":

And we're supposed to believe that George Bush, Tony Blair, and Michael Chertoff have just awakened to this fact? At a minimum, this is a further indictment of the incompetence of Bush and his cronies. They have done NOTHING, I repeat, NOTHING to deal with this threat even though security professionals have known and fretted about this for years.

I commented specifically on this two years ago on the Joe Scarborough show:

(Referring to Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the first World Trade Center attack in 1993) He got aboard the plane and built that device in the lavatory, took it back, put it under the seat, got off the plane, someone else got on board. The plane took off and it exploded in flight. So one of the gaps still in place is that we haven‘t come up with effective detector at screening checkpoint for liquid explosives.

Speaking of "doing nothing," the oh-so serious, to-be-trusted, terror busting Bush administration was once again letting its slavish devotion to Paris Hilton's many rounds of tax cuts (and penchant for big, pork-filled giveaways to political allies) get the better of its obligations to spend money in the right places:

As the British terror plot was unfolding, the Bush administration quietly tried to take away $6 million that was supposed to be spent this year developing new explosives detection technology.

Congressional leaders rejected the diversion of funds, the latest in a series of Homeland Security Department steps that have left lawmakers and some of the department’s own experts questioning the commitment to create better antiterror technologies.

Well, nobody knew about the threat of liquid explosives so you can't really blame them for cutting those funds. With all the wasteful spending emanating from the DHS, you'd think they could at least squeeze in a few million for this type of R & D.

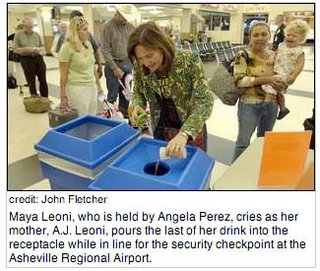

Finally, we get an appropriate cherry on top of this keystone-kops baked pie. Via Jim Henley, we see the Department of Homeland Security implementing measures at airports intended to safeguard passengers from the threat of this new bomb making capacity: the mixing together of various liquid agents so that they become dangerous explosives.

But get this: the means to protect the public from these potentially volatile liquids (whose destructive powers only accrue when mixed) is to either force all travelers to dump their liquid containers into trash cans (were the potential for mixing is, ahem, somewhat increased) or, alternatively, actually empty the contents into giant receptacles.

Let me repeat that: Passengers pour the contents of their liquid containers into one giant mixing bowl of potential explosive agents that only become dangerous...when mixed!Feeling safer?

Monday, August 14, 2006

Work, Not Cooperating

In the meantime, I give you Spencer Ackerman discussing an idea that has been a near-obsession around TIA for the entirety of its 2-plus year existence [emphasis mine]:

There's a bigger problem with his pitch: Lieberman isn't strong on defense at all.The phrase I have repeated ad nauseum is: the strength of a policy is in the results. Not the means used to achieve the ends - which if confused with the results, often leads to counterproductive misadventures. Ackerman puts is slightly more succinctly (the advantages of an editor?). Notwithstanding Haggai's well-reasoned caveat, my criticism of Israel's latest military engagement falls along these lines (as that discussion is being advanced by praktike).

Sure, Lieberman's a hawk. Since arriving in the Senate in 1989, he rarely met a U.S. military action he didn't like. And on numerous occasions, Lieberman's enthusiasm for war has led to enhanced national security, as with his votes for the 1991 Gulf War and the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. What's more, he also stood up for commendable interventions, like the NATO campaigns in the Balkans during the 1990s, when not many Democrats were willing to lend them unequivocal support.[...]

Indeed, Lieberman's judgment on defense questions is like that of a stopped clock: the hawkish position, applied consistently, has to be right sooner or later. What Lieberman is asking Connecticut -- and the Democratic Party, and the country -- to accept is that the only secure America is a bellicose America. And that position is a guarantee of future Iraqs.[...]

But belligerence isn't the same thing as wisdom -- and hawkishness does not always lead to a safer America.

This all ties into something that Kevin Drum began to address late last week. Said Drum, while discussing the notion that sometimes it is smarter to respond to provocation with less than a heavy-hand (as evidenced by the less than ideal results of the current Israeli/Lebanese conflict):

It's human nature to demand action following an attack. Any action. Counseling restraint in the hope that it will pay off in the long run is politically ruinous.Well, I'm not sure I'm smart enough to find the magic formula for this argument either. But I'll likely try, in vain, again. And again. Because it is crucial for us to understand this, regardless of my abilities as a communicator.

But our lives may depend on figuring out how to make this case. If it wasn't obvious before, it should be obvious by now that conventional military assaults are usually counterproductive against a guerrilla enemy like the ones we're fighting now. We can't kill off the fanatics fast enough to win, and in the meantime the war machine simply inspires more recruits, more allies, and more sympathy for the terrorists. It's not the case that conventional military force is always useless in these cases — the Afghanistan war still holds out hope of success — but as Praktike says, it usually results in a terrorism own goal.

Unfortunately, I'm not smart enough to figure out how to formulate this argument in an effective way. I wonder at times how Harry Truman managed the trick at the dawn of the Cold War, fending off the "rollback" hawks and convincing the public that containment was a more realistic strategy. But despite reading a fair amount about the era, I still don't know what the key was — though the presence of a sane faction in the Republican Party at the time was certainly a factor.

Honestly, if there is one thing that I could contribute to the world, one accomplishment that would make the endless hours spent blogging worth it, it would be persuading a handful of people of the wisdom of this proposition. And then maybe they persuade a couple themselves. And so on.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Standing on the Beach...

I have to admit, Sullivan has a point. Because if we could create a democracy in Iraq, that would pretty much spell the end for radical Islamist terrorism. Everyone knows that, while Iraq was not a major contributor to al-Qaeda's brand of terrorism prior to the invasion, after a peaceful and democratic Iraq emerged, then Iraq really would not be a major contributor to al-Qaeda's brand of terrorism.

Further, while democracy in nearby places such as Turkey, ongoing democratic works-in-progress in Afghanistan and Indonesia, and liberal democracies in farther away places like Europe and America, might not have been enough to convince radical Muslims of its appeal, once placed in Iraq, the forces of attraction would be irresistible.

Finally, as anyone from London to Madrid could attest, democratic societies do not produce Islamist terrorists. People born in democratic societies just don't grow up to be terrorists. Democracy is simply incompatible with such notions.

Why just look at the citizenship of those involved in the Madrid bombings, the London subway/bus bombings and those apprehended in the recent foiled plot to bomb commerical aircraft departing from Heathrow. A closer inspection of the nationalities of those involved in the most recent thwarted attack reveals the immunity granted to democratic societies [emphasis added]:

Er...uh...Britons? Converts? Hmmm. Allow me to consult my notes. In the meantime, though, I should point out that at the very least, by fighting the terrorists in Iraq, we insure that we don't have to take them on elsewhere. Actually, let me get back to you on that last point too....the Bank of England identified the 19 suspects by name and age. All were men between 17 and 35, and most seemed to be Muslim Britons of Pakistani descent. At least three of the suspects, though, were converts to Islam, according to residents near their homes; one of the suspects, Don Stewart-Whyte, 21, had traded a western life for an austere devotion to his new faith under the new name of Abdul Waheed.

Bin Laden: With Adversaries Like These....

Ned Lamont correctly observed that Lieberman adopted almost the exact rhetoric of none other than Dick "Perpetual Last Throes" Cheney. The guy with the 28% approval ratings - whose credibility is so low that even that number looks impressive. An interesting choice of role models for Lieberman, though it is consistent with his daft political touch.

As prakitke noted, Rudy Giuliani, Charles Krauthammer and many others are getting in on the action, trying to claim that the Iraq War represented an attempt to go on the "offense" against al-Qaeda, and that withdrawing troops from Iraq over the next year (as Lamont has favored) is an indication of unwillingness to fight al-Qaeda and their like-minded imitators.

Of course, this is spectacularly wrong. The war in Iraq has accomplished the opposite of showing determination to pursue and disrupt al-Qaeda. It is no secret that Bin Laden hoped to provoke an over-reaction by the US government, leading us into a protracted, excessive and aimless military conflict that would chew up assets, drain economic resources and tie down our military in an endless quagmire all the while providing a free, 24/7 satellite TV broadcast recruitment video for al-Qaeda to use to its benefit. Bin Laden thought that such an American blunder would occur in Afghanistan, but we averted that trap. The tragedy is, we then stepped into Iraq and pointed the gun squarely at Uncle Sam's boot and emptied the entire clip.

Cheney shows how little he understands about foreign policy (or how utterly dishonest he is) in his critique of the Democrats and Ned Lamont:

Mr. Cheney, in an interview with reporters on Wednesday, said that Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups were counting on Americans to adopt a weaker military posture, and that Mr. Lamont's victory indicated that "the dominant view of the Democratic Party" favored that weaker approach.This is exactly the opposite of what al-Qaeda wants. By and large, terrorists thrive when we adopt a heavy-handed military posture. There are some exceptions, like Afghanistan, where limited military force is necessary to destroy safe havens, training grounds and logistical centers. But those are, as I mentioned, exceptions. The war in Iraq, on the other hand, accomplished none of that - because those conditions did not exist in Iraq before the invasion.

As an unfortunate gift to Bin Laden, the Iraq war served to create a terrorist infrastructure and training ground where none existed before, and has been an invaluable asset to al-Qaeda from a PR perspective. We have done harm to our image in ways that al-Qaeda never could. But, Cheney would have us believe that al-Qaeda is worried that we're going to stop launching similar counter-productive, costly and futile military misadventures. Yeah, terrified I'm sure.

In the midst of this swirling whirlwind of misinformation, I thought it would be a good time to replay some of the findings of a survey of national security and counter terrorism experts that I posted about last month. Foreign Policy magazine, together with the Center for American Progress, conducted a survey of over 100 national security experts and terrorism analysts asking questions related to the struggle against terrorism and the Iraq war. The results are as follows [emph. mine]:

The United States is losing its fight against terrorism and the Iraq war is the biggest reason why, more than eight of ten American terrorism and national security experts concluded in a poll released yesterday. [...]

Asked whether the United States is "winning the war on terror," 84 percent said no and 13 percent answered yes. Asked whether the war in Iraq is helping or hurting the global antiterrorism campaign, 87 percent answered that it was undermining those efforts.

But Lamont's opposition to that war is something al-Qaeda wants. Michael Scheuer gives a re-cap of some of the particulars:

Yeah, I could see why al-Qaeda was so distressed that we went on the "offense" in Iraq. Bin Laden must be so very relieved that Ned Lamont was elected. I mean, someone like Ned Lamont, unlike Lieberman, would never endorse a military action like the war in Iraq. And we know how badly that worked out for al-Qaeda.One participant in the survey, a former CIA official who described himself as a conservative Republican, said the war in Iraq has provided global terrorist groups with a recruiting bonanza, a valuable training ground and a strategic beachhead at the crossroads of the oil-rich Persian Gulf and Turkey, the traditional land bridge linking the Middle East to Europe.

"The war in Iraq broke our back in the war on terror," said the former official, Michael Scheuer, the author of Imperial Hubris, a popular book highly critical of the Bush administration’s anti-terrorism efforts. "It has made everything more difficult and the threat more existential."

Thursday, August 10, 2006

These Colors Will Melt

Both countries have substantial populations of Arab and Muslim immigrants; both countries have domestic-security establishments willing to cut corners; both countries are either stomping all over the Ummah with troops or coddling our enemies as you prefer; the US still has and will always have major holes in its border security. Both countries have those crazy Imams you’re always reading about.

My tentative conclusion is that we’re simply dealing with a kind of law of small numbers here. The population of Muslims motivated to attack Americans in America is small, though current events are pushing the number up rather than down. Megaterror plots take time to mature. Most probably go wrong before execution (e.g. the Millenium Bomb plot in 2000). But could there be other factors?

While numbers matter, and that aspect should not be discounted, I do think there are other influences at play. James Fallows touches on some of those "other factors" in yet another impressive, and timely, piece in The Atlantic [emphasis mine throughout]:

The dispersed nature of the new al-Qaeda creates other difficulties for potential terrorists. For one, the recruitment of self-starter cells within the United States is thought to have failed so far. Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands are among the countries alarmed to find Islamic extremists among people whose families have lived in Europe for two or three generations. “The patriotism of the American Muslim community has been grossly underreported,” says Marc Sageman, who has studied the process by which people decide to join or leave terrorist networks. According to Daniel Benjamin, a former official on the National Security Council and coauthor of The Next Attack, Muslims in America “have been our first line of defense.” Even though many have been “unnerved by a law-enforcement approach that might have been inevitable but was still disturbing,” the community has been “pretty much immune to the jihadist virus.”

Something about the Arab and Muslim immigrants who have come to America, or about their absorption here, has made them basically similar to other well-assimilated American ethnic groups—and basically different from the estranged Muslim underclass of much of Europe. Sageman points out that western European countries, taken together, have slightly more than twice as large a Muslim population as does the United States (roughly 6 million in the United States, versus 6 million in France, 3 million in Germany, 2 million in the United Kingdom, more than a million in Italy, and several million elsewhere). But most measures of Muslim disaffection or upheaval in Europe—arrests, riots, violence based on religion—show it to be ten to fifty times worse than here.